EMDR and Gut Health: Exploring the Connection

Guest Blog Post by Beth Thibault, LCPC, LADC

My interest in gut health and chronic pain stems from personal experience. Following surgery, I encountered inflammation and deterioration of my gut health. After consulting numerous medical and holistic practitioners, it became evident that underlying processes were affecting my gut microbiome. This revelation led me to conduct further research, particularly after expanding my knowledge of how trauma and anxiety influence the body through eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) practices.

Over the years, I discovered striking connections between gut health and mental wellness. A pivotal moment in my journey occurred during a presentation by a physician who worked for the medical board, trying to regulate essential oils to the best of his knowledge. He revealed that 90 percent of serotonin and dopamine are produced within the gut. As a mental health professional with over a decade of experience, I found this information astonishing—and I continue to share it with clients, many of whom are hearing it for the first time.

The bigger picture: Understanding the cycle

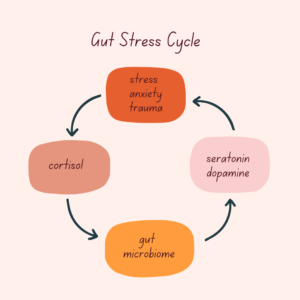

Stress, anxiety, and trauma are interconnected with both cortisol and the gut microbiome, forming a complex relationship:

Cortisol’s role in gut health and inflammation

Cortisol, often referred to as the “stress hormone,” plays a crucial role in the body’s fight-or-flight response, ensuring homeostasis during stressful situations. However, chronic elevation of cortisol, often caused by prolonged stress or trauma, disrupts the gut microbiome and contributes to inflammation. This cascade of physiological responses amplifies chronic pain, digestive issues, and mental health concerns.

Breaking the cycle

While maintaining gut health through diet and probiotics is key, EMDR providers can uniquely address this cycle by treating trauma and anxiety. EMDR techniques work to reduce cortisol levels by shifting traumatic memories from the reactive amygdala to rational processing. This intervention offers significant benefits in breaking the cycle and improving physical and emotional health. Below is an outline of how this author has utilized EMDR in clinical practice to work with pain or discomfort in the gut, phase by phase.

The EMDR process

- Assessment of client’s needs, possible targets and resources: During phase one of EMDR, the clinician conducts a biopsychosocial assessment, gathering information about the client’s history of trauma, medical background, current symptoms, and resources. Identifying the target issue, such as trauma and/or pain, is the next step, followed by identifying memories linked to the target.

- Education and resourcing: An additional resource to be implemented in phase two is a mindfulness body scan to help the client identify where pain is held in the body. This can assist in pinpointing areas of discomfort that may be linked to the trauma. The clinician then uses EMD to desensitize the emotional connection to the pain, helping to reduce its intensity and understanding where the physical pain rests. Education and other resources remain the same as when used in the standard protocol.

- Integration of positive cognition for pain management: Clients are encouraged to integrate a positive cognition that includes pain management as well as an empowered thought. This helps shift the focus from pain to healing. All other steps to light up the limbic system remain the same as presented in the standard protocol.

- Continued focus: If the Subjective Units of Disturbance (SUD) rating is not at a 0, the clinician will help the client focus on the body’s sensations, ensuring that the body’s response is addressed during processing. The clinician will continue with the standard protocol.

- Installing the positive cognition: The standard protocol is followed, but with an emphasis on incorporating positive cognition about the body’s health and healing, as well as the empowered thought, as mentioned earlier. This phase reinforces the body’s capacity for resilience and recovery.

- Body Scan: The clinician reassesses the client’s pain levels using the body scan as a guide. If the pain level is at baseline, the clinician will evaluate whether any new or lingering pain persists. Any changes in pain levels can provide valuable feedback for further treatment.

- Closure: Closure dialogue and investigate whether resourcing remains the same. The clinician may add pain references that might appear when reprocessing after the session.

- Re-evaluation: When re-evaluating for reactive behaviors and symptoms, the clinician will also assess for pain in the body.

Results and observations

In this author’s clinical application, EMDR has demonstrated notable efficacy in managing gut health conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Many clients report reduced anxiety, improved pain management, and decreased flare-ups. It is important to note, however, that symptoms may temporarily worsen before improving, a natural response I have encountered when addressing reactive behaviors through EMDR.

Studies conducted on the relationship between chronic pain and trauma utilized functional MRI (fMRI) testing and indicated that individuals with a history of childhood trauma exhibit heightened amygdala reactivity, contributing to increased vulnerability to chronic pain in adulthood (Martucci, et al., 2014; Mickleborough, et al., 2011). Additionally, early-life stress can impair prefrontal cortex function, reducing its ability to regulate emotional responses and exacerbating pain-related distress. Functional MRI (fMRI) studies have revealed distinct neurobiological changes in these brain areas, illustrating how trauma-induced modifications in amygdala-prefrontal cortex interactions may underlie the persistence of pain and emotional dysregulation.

Dispelling myths

A common misconception is that anxiety is the sole cause of IBS. When working with clients, it is essential to emphasize that anxiety may aggravate symptoms but is not always the underlying cause. Collaboration with medical professionals and a full workup remains vital for accurate diagnosis and comprehensive care.

Another misconception is that EMDR therapy is compared to mindfulness practices. Although mindfulness practices can be used for resourcing, it is important to emphasize that EMDR therapy is not a mindfulness practice, but instead a scientific approach with the goal of connecting neuropathways to memories.

Multicultural considerations

Diet and food intake vary across cultures, making it necessary to approach discussions on gut health with sensitivity. If dietary habits are unclear, focusing on cortisol management may be a more universally relevant approach. Please keep in mind that if there is a language or intellectual barrier, reprocessing might take longer, resulting in longer sets than the standard protocol.

The second brain

The gut is often referred to as the “second brain” due to its intricate relationship with the central nervous system. When the body experiences trauma, emotional memories are stored in the amygdala, triggering the fight-or-flight response. This response is not just a mental reaction but also a physical one. The increase in cortisol production during a traumatic event can disrupt the gut microbiome, promoting inflammation and digestive issues. This disruption leads to a vicious cycle—gut dysfunction and chronic pain contribute to an increase in stress, which in turn exacerbates gut imbalance and inflammatory responses.

The emotional and physical effects of trauma create a feedback loop where the body’s response to stress intensifies pain and discomfort. This heightened response can also disrupt the production of serotonin and dopamine, resulting in further deterioration of mental health. The interplay of trauma, gut health, and inflammation creates a complex environment where chronic pain and mental health issues reinforce each other.

Beth Thibault is a licensed clinical professional counselor and the owner of a private practice and wellness center in Maine. As an EMDRIA™ Approved Consultant and Credit Provider, she specializes in EMDR, with a focus on chronic pain and the gut health connection. With four years of experience in EMDR, Beth works with both children and adults, adhering closely to standard protocols while providing individualized care.She offers advanced consultation for professionals seeking certification, CIT consultation, and specialized guidance in EMDR applications. Beth Thibault also delivers approved training sessions on chronic pain and gut health, available both virtually and in-person. She is actively working toward basic training certification to further expand her educational offerings.

References

Depape, Keila. 2023. Childhood Trauma Increases Risk of Chronic Pain in Adulthood. McGill Newsroom Institutional Communications. https://www.mcgill.ca/newsroom/channels/news/childhood-trauma-increases-risk-chronic-pain-adulthood-353822

Martucci, K. T., Ng, P., & Mackey, S. (2014). Neuroimaging chronic pain: what have we learned and where are we going? Future Neurology, 9(6), 615–626. https://doi.org/10.2217/fnl.14.57

Mickleborough, M. J., Daniels, J. K., Coupland, N. J., Kao, R., Williamson, P. C., Lanius, U. F., Hegadoren, K., Schore, A., Densmore, M., Stevens, T., & Lanius, R. A. (2011). Effects of trauma-related cues on pain processing in posttraumatic stress disorder: an fMRI investigation. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience (JPN), 36(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.080188

Raffaeli, W., Tenti, M., Corraro, A., Malafoglia, V., Ilari, S., Balzani, E., & Bonci, A. (2021). Chronic pain: What does it mean? A review on the use of the term chronic pain in clinical practice. Journal of Pain Research, 14, 827–835. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S303186

Shapiro, F (2018). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic principles, Protocols and Procedures (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Tesarz, J., Wicking, M., Bernardy, K., & Seidler, G. H. (2019). EMDR Therapy’s Efficacy in the Treatment of Pain. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 13(4), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.13.4.337

Wertheim, B., Aarts, E. E., de Roos, C., & van Rood, Y. R. (2023). The effect of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) on abdominal pain in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (EMDR4IBS). BMC Trials, 24: 785. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-023-07784-1

Yang, S., & Chang, M. C. (2019). Chronic pain: Structural and functional changes in brain structures and associated negative affective states. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(13), 3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20133130

TeBack to Focal Point Blog Homepage

Additional Resources

If you are a therapist interested in the EMDR training:

- Learn more about EMDR therapy at the EMDRIA Library

- Learn more about EMDR Training

- Search for an EMDR Training Provider

- Check out our EMDR Training FAQ

If you are EMDR trained:

- Check out the EMDRIA Let’s Talk EMDR Podcast

- Check out the EMDRIA Focal Point Blog

- Learn more about EMDRIA membership

- Search for EMDR Continuing Education opportunities

If you are an EMDRIA™ Member:

- Learn more about EMDR Consultation

- Find clinical practice articles in the EMDRIA Go With That Magazine®

- Search for articles in Journal of EMDR Practice and Research in the EMDRIA Library

Date

June 13, 2025

Contributor(s)

Beth Thibault

Topics

Medical/Somatic